It’s been an eventful past few days and a rather interesting New Year’s Eve. Last Thursday, I was at work trying to service some equipment at low tide and needed to walk through an intertidal area. The site was rather rocky, covered by thick mats of Sargassum seaweed during the blooming season. As I was making my way through the water, I felt a sudden stabbing pain pierce through the top of my left foot. Gingerly lifting my foot out of the water to take a look, I noticed a spine embedded in my booties, still attached to wispy trails of blue flesh. A little in awe that the barb pierced through the thick layer of neoprene and rubber, I looked around for the culprit but saw nothing in the murky waters.

To be honest, I felt a bit of relief when I saw that dash of blue because I knew I hadn’t stepped on something worse. The blue was a telltale sign that the poor spooked guy was a blue-spotted ribbontail ray (Taeniura lymma). This is not to be confused with the blue-spotted stingray (Neotrygon kuhlii), which has black and white bands on its tail and was unlikely the culprit. Stingrays can cause a lot of pain, but unless the sting is delivered straight into major organs or causes severe blood loss, it’s unlikely to cause death. While it was unlucky that I happened to step onto a stingray, I was immensely lucky it wasn’t something worse. There are a few highly venomous sea creatures in Singapore such as cone snails, stonefish and the rarely-sighted blue-ringed octopus (which purportedly has enough venom to kill 26 adults in minutes).

I’ve put together a list of questions asked by friends and medical staff in the hopes that if anyone is accidentally stung by a stingray, they can easily understand what’s happening to them and how to handle it. While writing this, I also learnt quite a few new things about venomous sea creatures and stingrays. I sincerely hope that some of these answers spread awareness instead of blindly antagonizing stingrays and other venomous fish. While stingrays get a bad reputation from notable deaths caused (Sorry Steve Irwin), they are behaving the way any animal does when it feels threatened and is trying to protect itself. If anything, this encounter has become a reminder that when we venture into the sea, we are entering a different world -their world- and it’s vital that we respect it.

Q: Does it hurt when a stingray stings you?

Probably the first question anyone asked and the answer is…Duh!? For me, the pain was bearable at the start but progressively worsened over the next few hours. The peak was almost four hours in when I was waiting for my x-ray and blood test results at which point I begged the nurses for more painkillers. Some extreme accounts liken the pain to a gunshot wound but I think that’s a bit dramatic. My point is, even if you feel the pain is bearable at the start, don’t be a hero and seek immediate medical attention. You’ll thank me four hours later.

Q: How large was the barb and which part of your foot did it pierce through?

It went between the extensor tendon and the third metatarsal head of my left foot. The blue-spotted ribbontail ray is one of the smaller stingray species and the total length of the barb was 5 cm (around 2 inches). Around half of the barb was lodged in my foot.

Q: Why didn’t you just pull out the sting/barb in your foot?!

Stingray barbs have backwards-facing spines. Pulling it out would have caused further injury as the flesh is torn out or may even cause excessive bleeding. It’s best to leave it in and seek professional medical attention. In my case, it required surgery that took no more than two hours to remove it.

The barb in my foot after my diving booties were cut and removed

Q: Are stingrays poisonous?

Stingrays are venomous, not poisonous. The easy way to remember the difference is — Poison: You bite it, it harms you. Venom: It bites you, it harms you. Venom is injected through the bloodstream whereas poison is ingested and harmful when it is absorbed by your digestive system. An example of a venomous sea creature in Singapore would be the yellow-lipped sea krait and an example of a poisonous sea creature would be the map pufferfish. Although highly venomous, sea snakes in Singapore are shy creatures that feed mainly on fish. Furthermore, these snakes are rare locally with some species listed as locally endangered. Meanwhile, pufferfish have toxins on their skin and in their internal organs, requiring expert preparation for consumption. Cases of pufferfish poisoning occur but are uncommon.

Q: What type of venom is found in the sting?

According to an article on Venomous Fish Stings in Tropical Northern Australia, “Stingray wounds have the greatest potential to cause necrosis and infection.” While the barb can be easily removed and leaves a small wound in my case, the main concern was the aftercare of the wound to prevent and monitor infections.

Stingray venom contains a whole host of different proteins known to be cardiotoxic, hemotoxic and neurotoxic (affects the heart, red blood cells and brain). One of these compounds includes bibrotoxin, which causes blood vessels to constrict leading to pain and inflammation. Another source shows stingray venom has fibrinolytic and anticoagulant properties that exacerbate blood loss. The thin layer of skin surrounding the spine of the stingray not only introduces venom but exposes the wound to other bacteria and microorganisms. In some cases, this can lead to further bacterial infections such as tetanus.

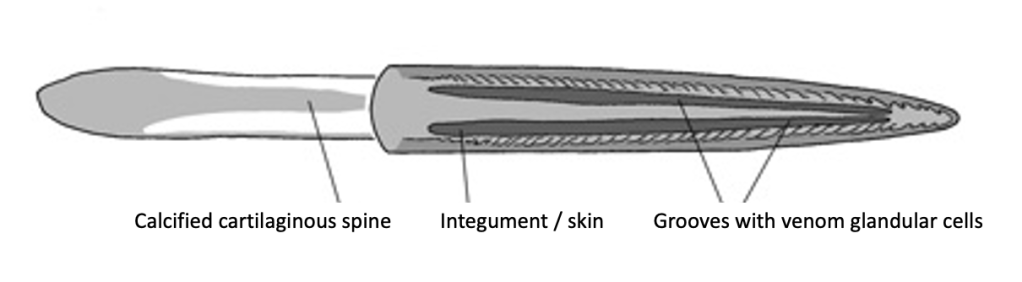

Q: How is the venom delivered from the barb?

Stingray venom isn’t produced by venom glands but by two long grooves under the skin that contain venom-secreting glandular cells. The skin acts as a sheath and peels back when the barb is thrust into the victim, thus releasing the venom.

Q: Where is the sting on stingrays? How do they sting? Will the stingray die after using its sting?

One common misconception is that the entire length of the stingray’s tail is the sting. That’s not correct, the barb of the stingray is usually located near the base of the tail that connects with its main body. It rests on the top of the tail and is primarily made up of keratin, the same protein that makes up our hair and nails. When stingrays sting, they whip their tail around to lodge the barb into its assailant’s flesh and the barb breaks off. Thankfully, the stingray will not only survive this ordeal but is also capable of growing its barb back within a year or so, with some observations of stingrays regularly shedding their barb 2-3 times a year.

Q: Why do stingrays and other fishes sting?

Most marine and freshwater fish use their stings for defence with less than 2% of fish known to use venom for predatory purposes. Similar to the rest of the majority, stingrays do not use their sting for any other purpose apart from self-defence. The blue spots on the ray that stung me is actually a great example of aposematism or warning colouration that is used to deter predators. It is used as a last resort because having to regrow a barb is energetically costly.

Q: How did fish evolve their stings? Which parts of these fish are venomous?

There are more than 2900 species of venomous fish worldwide in both freshwater and marine habitats, most of which use venom for defence and the minority for predation or competition. What surprised me was that these venom systems are likely convergently evolved, meaning that different lineages of fish evolved venom independently as an adaptation. Fish seem to engineer and evolve a similar solution to the problem of being eaten by predators.

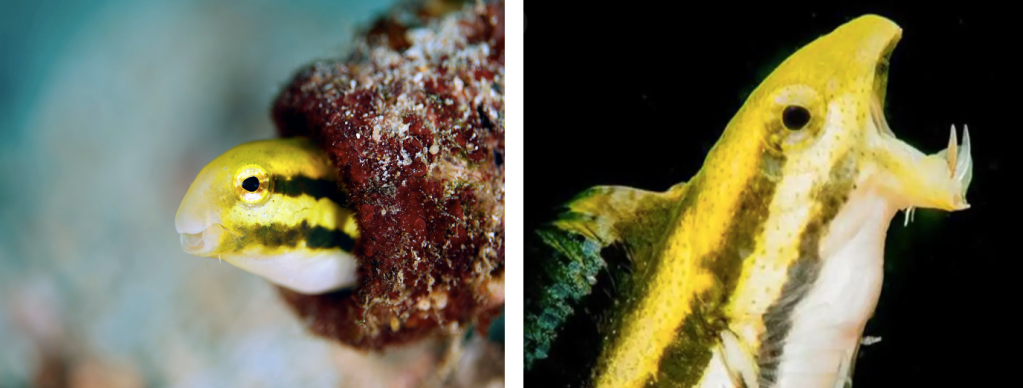

Some other notable types of venomous fish include catfishes, which represent 58% of venomous fish species, because of its large diversity. Meanwhile, venomous fangblennies are unique in that they inject venom through their canine teeth instead of spines like most other fish. These fangblennies are tiny, no larger than your finger. When ingested by a predator, it bites its predator from the inside and stuns it into opening its jaw and gills, then swims away out of the predator’s mouth unscathed.

Striped Blenny (Meiacanthus grammistes) – A type of venomous fangblenny that looks really cute because it smiles while peering out of small holes in corals or bottles, but also has opioid toxins that cause a drop in blood pressure. (Photo credits here and here)

Q: How do I avoid being stung by all of these creatures?

The easiest solution is to keep out of the water, but hey, that’s not entirely viable is it? The next best option is to wear proper protective clothing such as booties when exploring rocky or intertidal areas. Avoid walking in places with low visibility. If you must, shuffle your feet slowly when walking in submerged sandy areas with poor visibility. Most animals will move away when they sense a large animal coming their way.

Q: What should I do if I get stung by a stingray? What kind of medical attention did I receive?

Firstly, stay calm and signal for help so you can make your way to shore or the boat as safely and quickly as possible. Assess the severity of the wound — Is it bleeding profusely? Is the sting intact? Some tips for first aid and treatment of stingray stings are listed in the Clinical Toxinology Resources, which I’ve copied below. This is a really good resource for bites and stings with the appropriate first aid for each type of animal.

- The victim should immediately leave the water.

- Loose broken stings in limb wounds, away from major blood vessels, can be gently removed. If force is required, leave the sting alone. Stings to the chest and abdomen, in general, should be left untouched, as removal may cause further damage and endanger the patient. In particular, stings to the chest wall, near the heart, can prove lethal and inexpert removal of the sting can precipitate rapid collapse and death.

- The wound should not be rubbed, or stings crushed as this may worsen the local effects of the sting.

- There may be significant tissue injury and bleeding. Staunch bleeding by application of local pressure. If necessary, apply a bandage to maintain local pressure over the wound. Only if there is severe bleeding, caused by damage to major blood vessels, apply a tourniquet above the wound, to a single-boned part of the limb (thigh for leg; upper arm for arm) to control the bleeding. Tourniquets are effective at controlling bleeding, but in doing so, deprive the limb of oxygen, so cannot be left on for more than 30-45 minutes, or they will cause permanent injury. They therefore require regular release for short periods.

- The use of immersion in hot water is controversial. Some authorities suggest that immersing the stung limb in hot water may reduce pain. Others suggest it is useless. For stingray injuries, experience suggests hot water immersion is often very effective at providing pain relief and therefore should always be considered. However, it is potentially hazardous, if used incorrectly, as it may cause burn injuries. If used, immerse the opposite limb to that stung in water which is hot, but bearable with prolonged contact. It should not be so hot as to cause pain. Then immerse the stung limb as far as necessary to include the sting area. Keep both limbs in the water for 15-20 minutes, providing there is relief of pain. If there is no relief of pain in this time, abandon the immersion. If pain has subsided, it may return on removal from the water, in which case, reimmerse for a further 15-20 minutes. Repeat this process up to 4 times. If after 1-2 hours, the pain is still severe on removal from hot water, then other forms of pain relief may be required, but these will require medical intervention.

- Transport the victim to medical care as soon as safely possible, except where the wound is very minor and pain has been easily and fully controlled and the victim has current anti-tetanus immunisation.

- All stingray wounds to the chest, abdomen, or neck are potentially very serious, even if the wound looks minor and no sting barb is visible. All such cases require urgent hospital assessment.

Q: What role do stingrays play in the ecosystem?

Stingrays function as bioturbators, stirring up sediments as they hunt for crustaceans and molluscs. This process helps oxygen disseminate into the ocean’s sediments and helps with nutrient cycling. Populations of blue-spotted stingrays have actually been increasing, and one possible reason could be the collapse in shark populations, their main predator. According to the WWF Sustainable Seafood Guide, all shark and ray species are considered unsustainable. It’s unclear to me why these rays are considered unsustainable though, but my guess is that the methods of fishing can be rather destructive? In any case, I have no intention to take revenge with a plateful of sambal stingray.

Q: Can the venom from stingrays be useful?

Our understanding of venoms in the marine environment is still limited as most studies so far have focused on terrestrial snakes. What we do know about venoms in general, is that they are potent and highly targeted, consisting peptides that can alter cell function rapidly, properties that are useful to drug development. For instance, peptides in cone-snail venom are used to slow down prey by causing paralysis and pain-suppression. This led to the creation of Prialt, a painkiller that prevents neurons from communicating with each other that is reportedly 1,000 times as powerful as morphine. Dr. Mandë Holford’s laboratory focuses on “the power of venom to transform organisms and to transform lives when it is adapted to create novel therapeutics for treating human diseases and disorders”. The medicinal and other applications of marine life show that the conservation of biodiversity can benefit humanity in ways we don’t often expect. Each time we lose a species, we also lose an important player in ecosystems, the potential it has for biochemical compounds and so much more.

This post started off being an efficient way to answer all the questions I’ve had about my foot (and more importantly, to reassure my mother I would be alright). Little did I realise how fascinating the world of venom is and how little we know of it. I suppose the silver lining of being ordered bed rest for two weeks, is that I’ve gained time to ponder on how I landed myself in this situation, what I could’ve done to prevent it and finally, marvel at nature with its insane adaptations. I can’t wait to be back in the water.

Came across your article this morning via a post from a friend in Facebook.

Started reading out of curiosity (kpo) while on my ride to work and pleasantly surprised by the information included. Thank you!

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing. Very interesting!

LikeLike