One of my favourite creatures to look at when diving are feather stars (Class Crinoidea). They just seem so alien-like and other-worldly sometimes that I can’t help but marvel at them. Here’s a super cool video I took of a swimming crinoid at Pescador Island near Moalboal, Cebu.

Most of the crinoids I found unfurled seemed to be shaded by overhangs or were found deeper along the wall where there was much less light.

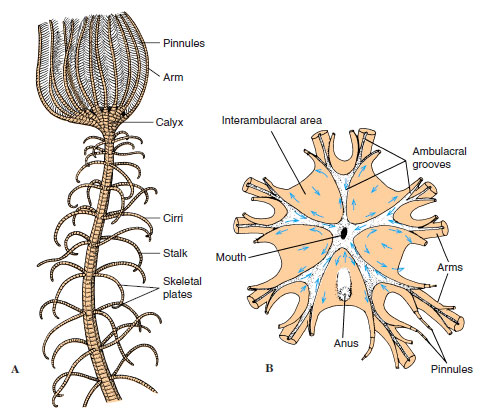

Some deeper water crinoids have stalks and are also known as sea lilies because of a faint resemblance to the flower, but they’re hardly plants at all! A distant relative to sea stars, sea cucumbers and sea urchins, they’re in the Phylum Echinodermata which comes from the Greek ekhinos meaning “hedgehog” and derma referring to “skin”. Though they may look nothing like each other at a glance, the key common characteristic among these creatures is the presence of tube feet, a unique type of symmetry where their bodies can be divided five ways and a calcareous skeleton.

Crinoids are fascinating for so many different reasons. Firstly, they’re considered living fossils, having been on earth since the Ordovician period approximately 490 million years ago. In comparison, Homo sapiens (aka us) have been around no more than 300 thousand years ago. Parts of their skeletons are so hardy that they’ve even been used in jewellery and are associated with the rosary of St Cuthbert, a medieval saint in Northern England.

Crinoids can have as many as 200 arms (arms are usually in multiples of five) which they use to crawl along the seafloor or even swim through the water column. They feed primarily on plankton, detritus and other particles floating in the sea by filtering it with their mucus-coated outstretched arms, moving it to the center of their bodies where the mouth is. Feeding usually takes place at night when more plankton is available in the water, so these creatures usually curl up in the day. Like sea stars, they can also regenerate their limbs or detach them at will to evade predation. One thing I don’t envy, however, is that their mouth and anus are just side by side.

There’s also some evidence to suggest that feather stars are hardy creatures that could be more resilient to sea temperature rise than other marine life. When limbs are lost, feather stars can regenerate their arms faster with a 2°C increase in water temperature. They also don’t seem to have many natural predators, as they are unpalatable to most fish though sea urchins have been recorded munching live feather stars.

Why feather stars fascinate me the most on dives (aside from all these cool facts) is that you can often find a treasure trove of different well-camouflaged critters hiding within its tentacles. Often, these tiny fish, crabs and shrimps match the colours of their host. There’s just something so remarkable about symbiosis that I’m always drawn to. Knowing that some of these animals are found in selected species of feather stars makes me treasure the finds even more.

During our dive in Mactan and Moalboal, I loved peering into the tentacles of crinoids to see if I can find any unique creatures living within the tentacles of these creatures. It’s especially difficult to take a good picture of anything living in the feather stars for three main reasons:

- Everything living in feather stars is tiny (less than 3 centimetres) and incredibly well-camouflaged.

- The feather stars have brittle arms which can break off if you accidentally touch them. (It’s important as a photographer to not destroy or hurt any animals you’re photographing!)

- The arms tend to curl up when exposed to bright lights, further hiding the animals that live within them (They’re nocturnal remember!?)

So imagine the sheer joy I had when I was lucky enough to snap a quick couple of photos of this cryptic shrimp!

Sometimes you don’t get so lucky. This shrimp with a distinct white dot on its back was also very well-hidden among the arms of the feather star. I was trying to photograph it quickly but it leapt inside before I had time to change my focus settings.

I got so excited when I found this clingfish, but it was almost impossible to get a good photo of it because its head was facing inwards towards the center of the feather star.

My best guess would be that this is the crinoid clingfish (Discotrema crinophilum) which grows up to a maximum length of 5cm. This particular species of clingfish is usually found in close association with the feather star species Oxycomanthus bennetti. A pretty useful species, it has been known to produce the compound comaparvin, useful in the medical field for its anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects. At first, I thought clingfish were a type of goby. I was wrong. Apparently, they’ve got their own family Gobiesocidae. Clingfish have a suction disc on their bellies formed by the pelvic fins and surroundings folds of flesh, reminiscent of mudskippers, which can withstand forces more than 150 times their body weight. Their suction is so strong and structurally impressive that they can cling on to surfaces even after they’re dead. Scientists studying this mechanism discovered that the secret lies in microvilli around the edges of the disc that they can help inspire better designs for man-made suctions. Extra note: This new species of clingfish was found with more than 1800 teeth.

I’m still trying to figure out how to take better pictures of these animals so if anyone has tips do feel free to share them. Also, would appreciate help with identifying the crinoid species as well. Crinoids are so difficult to identify because many of the morphological characteristics are often obscured, and single species can sometimes come in a range of colours. *Welp*

More wacky creatures to come from Moalboal next time!

Leave a comment